Recent journalism

Part Chimp feature, for The Quietus

“I just think it’s quite satisfying to hear someone just fucking do something really simple. It just goes down every single fret [on the neck of the guitar] – that’s it! Even dogs could quite like that song, I imagine. But also, my avant garde classical musician mate does as well. He couldn’t believe it. ‘Did youse just do a song where the notes all go downwards?’”

Hotline TNT review, for The Guardian

Where previous albums had been one-man affairs, with Anderson overdubbing layer upon layer of guitar and synth on his lonesome, the presence of other musicians in the room has shaken up the paradigm. Their trademark walls of fuzz remain, but Raspberry Moon also fields tracks such as Break Right, on which the happy/sad melodies flourish with space to breathe, and the lush Lawnmower, which is practically unplugged (save for a keening thread of feedback in the distance) and utterly lovely for it.

Sly Stone feature, for MOJO

“Sly was on his waterbed, unconscious,” remembers Andy Newmark. “I said, ‘I hear you need a drummer; I’m the guy.’ He said, ‘OK, play.’ I closed my eyes and played what I thought was a funky beat. I opened them again, and Sly was dancing to my beat. He looked happy. He said, ‘You’re the new drummer.’” Newmark had been a huge Family Stone fan. “The band were magic,” he says. “But by the time I got there it was just Sly by himself. I arrived at the point where he was descending the mountain he’d climbed, into the darkness.”

The Messthetics feature, for The Quietus

“Everybody keeps calling me, thinking we can fix this Trump problem somehow,” grins Canty. “They’re all like, ‘You know, this would be a great time for Fugazi to come back’. And I don’t know what they think we’re going to be able to do about this. But I do appreciate the idea that we have superpowers.”

Cypress Hill feature, for The Independent

“That gangbanging life, there’s only a few outcomes,” B-Real says. “You either get caught in a shootout and die or end up paralysed, or you end up in jail your whole life. Or you get lucky and you get out of it. I don’t have any good memories of those days, except the day we got our record deal. That was the beginning of our escape from all that.”

Pete Shelley feature, for The Independent

Shelley – who was bisexual – wrote love songs without gender. Bob Mould, of pioneering US band Hüsker Dü, and also a queer punk songwriter, was deeply influenced by Shelley’s “fast, short, catchy songs about sexual confusion”, and told me that hearing Buzzcocks was “an epiphany for me, for showing me the power of non-gender-specific love songs”.

Sly Stone obituary, for The Guardian

The year closed out with a further triumph: the standalone single Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin), on which the Family Stone’s Larry Graham reinvented bass guitar by slapping and plucking his strings with percussive fury. This was heavy street music, Sly’s homilies of peace and hope replaced by something more uncertain, more confessional. Stone had signalled the wind-change that July with Hot Fun in the Summertime, a candy floss cloud whose doo-wop croon doubled as an account of a summer torn up by protests and riots. But Thank You made the disquiet explicit and detailed the riot going on within Stone, as he wrestled with the devil, ruminating that, “Dyin’ young is hard to take / Selling out is harder.”

Marc Ribot feature, for The Guardian

“We rehearsed 60 to 70 songs. And Tom could call off any one of those, or something we hadn’t rehearsed, and you had to roll with it. Tom was a demanding bandleader – he needs stuff to groove, and if the band is being wishy-washy, it wounds him personally and physically. You’ve seen footage of him in concert, banging the mic stand on the stage? That’s not a gimmick, that’s him telling us to get with the program. But he was always respectful. Tom understood the difference between a musician and a servant.”

I’m Being Good review, for The Quietus

36 years into their mission to boldly embed themselves inside rewardingly thorny knots of riff, Brighton-based mavericks I’m Being Good’s fascination for the delectable complexities within subterranean noise thrives unabated. Their ninth full-length is the sound of insatiable curiosity on the prowl, an exercise in just how many dangerous twists and occasional jump-scares this kind of post-math, post-prog, post-post-rock music can encompass.

Pink Floyd feature, for MOJO

Waters took the lead on this embryonic new project. “The ‘big idea’ came before quite a number of the lyrics,” he recalled to MOJO in 2006. “I remember explaining it to the rest of the band: that the whole record might be about the pressures or preoccupations that divert us from our potential for positive action.” More recently, he’s described himself as having been fired up by “a strong, compelling notion that we could make an album about life, about feelings, the human condition and things that impinge upon us.”

The Roches feature, for MOJO

“We felt defeated, so we went down to Hammond, Louisiana, where a friend had started a kung fu temple. We gave up playing music, but that’s where Maggie wrote Hammond Song. I was 21, and I felt like a complete has-been. A year later we returned to New York and tended bar at Folk City. Suzzy was studying, and when she’d visit us in the city that winter we’d all sing acapella Christmas carols at bars and in the streets.”

Pink Floyd feature, for The Independent

Waters assumes control – a move that isn’t without controversy, but helps shape Pink Floyd’s output throughout the rest of the Seventies. “Roger’s a brilliant architect of music,” says Wilson. “He pulls the band towards these conceptual rock moves, tethering them to the structures and the architecture of the music. But they had to go through this space-rock period first, to arrive there.”

Deerhoof review, for The Quietus

Noble And Godlike In Ruin is as gleefully perverse and perversely gleeful as anything in their catalogue, swinging between pop and noise like they aren’t opposed concepts, but rather points of equal value along a spectrum that the band ricochet across with sublime abandon… a hurricane of anarchic invention and unforced tunefulness, often at once.

Tunde Adebimpe feature, for The Quietus

“I have a very hard time making the same thing twice. I’m not content to find my version of Warhol’s soup can and run off endless copies of it. When I was younger, people would ask me, ‘When are you gonna settle on a style?’ And I couldn’t. I like looking at different things, taking in different ideas and styles and making them my own. Maybe my style is a bunch of different things sewn together?”

Chaka Khan feature, for The Guardian

“I’ve talked about doing a poetry book; I just can’t find all the scrap paper I’ve been writing my poems on! When I’m in creative mode, I need somebody to snatch those papers up before I go on to the next sheet! But I’ve got to start putting all that junk together and see if it inspires anybody, because sometimes the most disorganised stuff can be the best you’ve written. Life is inspiration to me – it’s like a bag of chips and popcorn, a major mix. I’m never at a loss of stuff to write about.”

Celia Cruz feature, for The Guardian

Whether exiles themselves or simply economic migrants, many in the concert audience – just like many in her fanbase across the Latin American diaspora – sensed the sadness beneath her words, the vulnerability within the strength. They crowned her the Queen of Salsa. “Celia had power in a male-dominated world, she changed the game,” says Cuban singer Daymé Arocena. “She had no interest in the comfort zone.”

Brainiac feature, for The Quietus

“We loved wild Japanese effects pedals – we didn’t like anything mellow, and were always like, ‘What happens when you when you turn the dial all the way up?’ ‘Hot Metal Doberman’s’ was the first track where he decided to layer several different vocal tracks over each other – he was like, ‘I can be three different characters in the same song!’ And it’s got a great opening line; it basically announces the troublesome presence of the album: ‘Whatcha gonna do about me?’”

Andy Kaufman feature, for The Independent

The wrestling was an extension of an earlier nightclub bit in which Kaufman would be heckled by an “audience member” (actually his friend Laurie Anderson) and they would end up wrestling onstage. The bit could get violent – a jeopardy that both Kaufman and Anderson relished. “I loved that he’d subvert this idea of this ‘perfect’ America,” Anderson says. “We live in the most violent country in the world. Andy was a mirror, and people didn’t like what they saw a lot of the time.”

Angie Stone obituary, for The Guardian

Stone was a contemporary of the neo-soul uprising led by friends and collaborators D’Angelo, Erykah Badu and Musiq Soulchild, but her age and experience gifted her music a superior weight and authority. Stone Love opened with a riff on the Supremes’ titular hit and then quickly revisited the boudoir where Mahogany Soul’s charmed break-ups and make-ups occurred (on Stay for a While, a delectably slow-burn suite of longing and lust, Stone got carnal with Anthony Hamilton over molasses-sweet swing).

Throwing Muses review, for The Guardian

There’s not a note wasted across these nine tracks, which conjure a dark, parched ambience akin to Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged session: that same austerity and tension. It suits these vignettes of American subterranea – blurry but resonant snapshots of lives becoming unhemmed, with violence often on the horizon.

John Reis feature, for The Guardian

“As a kid, I thought Live and Let Die was the biggest song ever. So huge sounding. I approached Rocket From The Crypt with the mindset that more is more – the more people onstage, the bigger the sound will be. And I love how the horns sit with the guitars – it all sounds like one massive instrument. It just has this undeniable girth.”

Lonnie Liston Smith review, for The Quietus

It was while working on Thembi that Smith first played a Fender Rhodes, and while fiddling with its many knobs and switches he fell upon the warm, meditative buzz that characterises that album’s opening piece, ‘Astral Travelling’. It was 1971, and to be a bit ‘woo’ weren’t no thing. Smith was a regular patron at Weiser Antiquarian Books, a New York staple he remembered as having “books on every religion, all philosophies. It was nothing to enter the bookstore and see Sun Ra, John Coltrane, looking at certain books. I was studying everything.”

Horsegirl review, for The Guardian

The album feels almost clockwork: every element machine-tooled, a place for everything, and everything in its place. But there’s no coldness here, the poignancy only accentuated by the poise with which these songs are delivered, the 7/8ths of the iceberg further revealing itself with each play.

Yasiin Bey feature, for The Guardian

“We had optimism and youthful naivety. Talib and I were continuing great traditions laid down by our elders – Gil Scott-Heron, Curtis Mayfield, Coltrane. I felt for sure we were doing something special. We knew radio programmers didn’t wanna play our pro-Black shit while they were trying to sell skin cream. We knew we weren’t going to be media darlings. But then we kinda ended up being that, low-key.”

Roberta Flack obituary, for The Guardian

Flack sang like she was equally conversant with the ecstasy of faith and the agony of life. The dignified richness of her vocal was tempered by the subtly volcanic power she displayed on her reading of To Sir With Love off Lost Takes – a not-so-quiet fire that always resided within her.

Bob Dylan feature, for The Independent

The Band needed redemption as badly as Dylan, and all involved hoped renewing their working relationship might invite lightning to strike once more. They entered LA’s Village Recorders in November 1973 and taped Dylan’s 14th album Planet Waves – his first for Asylum – over a whirlwind three days. It would prove Dylan’s best-received album in years, and “Forever Young” remains one of his most loved songs. Still, everyone knew that the road was where Dylan would truly affirm his renaissance.

Led Zeppelin feature, for The Independent

“We wanted to demystify that ‘Viking’ image of Led Zeppelin as these marauders laying waste to villages. Forget all the myths – the private jets, the drugs, the stuff bands like Mötley Crüe and Warrant thought Led Zeppelin was about. This is the beginning – the least-known part of the Led Zeppelin story, one shrouded in mystery.”

The Locust review, for The Quietus

Rock & roll assaulted existing senses of taste and decorum, existing understandings of song form and acceptable sonic frequencies for entertainment purposes. Like any controlled substance worth abusing, it left users endlessly grasping to re-experience that first high, that original shock of the new. At the start of this century, few redelivered that shock as well as The Locust.

Kim Deal interview, for MOJO

“When my mom stopped me in the hallway and said, ‘Are you my baby?’, what was so sweet about it is that, she didn’t know what sisters and cousins were anymore. She doesn’t know my fucking name. But she knows that I look more than familiar to her. It’s more than, like, ‘Who the fuck are you?’ She meant, ‘Are you my baby?’ Even with the mind completely gone and all notion of what a family might be and what relations are, there’s still some umbilical cord, like, ‘Were you my little baby doll?’ And I thought that was sweet. When she said that, I knew that would be a beautiful sentiment that I wanted to live in.”

Kim Deal review, for MOJO

Deal ascribes her slow pace to a hazy perfectionism on her part. Though she says she’s always writing, she told me a decade or so ago that “avoiding cliché” was paramount, suggesting that for every song we get to hear, there are dozens more lying rejected in the demo pile. That, for Deal, songwriting is a slow process of honing, of homing into that unique voice so recognisable from her work to date, a voice that rings so clear, and funny, and sad, and with deft power here.

Mos Def essay, for The Quietus

It’s a fierce, game-changing record, a savage display of talent from a young artist ready to take it all on. It’s aged extremely well, its blend of hip hop and neo-soul prescient, its lyrical and philosophical content of a piece with the modern-era thinking that the same clueless chodes who derided Mos then as a “mummy’s boy rapper” would now dismiss as “woke”. But Black On Both Sides is woke, as in alive, as in thoughtful, as in restless and ready to fuck shit up. Who wouldn’t have gambled on Mos Def as a star of the future, if not already the right now?

Will Cullen Hart obituary, for The Guardian

While Hart and Doss began work on a third Olivia Tremor Control opus, it remains uncompleted. Hart struggled with his MS, which he said had “destroyed” him. “Recording every day? I can’t do that any more. There are these buzzing sensations that won’t stop. It’s horrible.” Then, in 2012, Doss died suddenly of an aneurysm. And while Doss had completed all of his vocal tracks for the new record, for years Hart couldn’t face finishing the album without him. “Days after Bill passed, I realised I couldn’t keep doing this. I needed to let it go.”

Lori Goldston feature, for The Quietus

“Playing the big venues with Nirvana was very nerve-wracking at first, and then I really got to like it. It was just very festive – there were just really, really happy teenagers everywhere, thousands of really, really happy teenagers. Which was great. I like teenagers. And when they’re happy, they’re really happy. So it was pretty cheerful, really.”

Digable Planets feature, for The Guardian

“Black American music – hip-hop specifically – co-signed experiences I was having in America as an Afro-Latina girl. It was everything to me – I needed it to survive. I’d begun writing down my own observations on the world. When hip-hop came into my life, I realised: ‘I can turn these words into rhymes now’.”

Soweto Kinch feature, for the Royal Festival Hall

“There’s this international nexus of terrifying wars with no immediate end in sight, but I don’t think things are going to end as darkly as everyone expects. Maybe this is just the lunatic optimism of a jazz musician. But a lot of us are deeply offended by how the world is run, and are craving it to be reconstructed in a different way.”

The Beatles feature, for The Independent

“Lennon loved how rock’n’roll was rooted in Black music,” nods Tedeschi. “The establishment had been trying to stamp out rock’n’roll from the very beginning because the innuendo in the lyrics and the way the young people moved their bodies made Wasps so uncomfortable.”

Huggy Bear feature, for The Guardian

“We defined ourselves by what we loved, and also what we hated and despised,” says Rowley. “Our ethics were from left-field feminism, queer politics, situationism. We wanted to carve away all we found terrible and corrupting. We agreed we’d only exist for three years, and then split.”

Phil Elvrum interview, for The Guardian

“Geneviève and I had both been artists, obsessed with our creative lives,” he says. “That was our focus, our devotion, our identity. But when she died, I asked myself: why had drawing at a table 16 hours a day or making all these dinky little LPs been so important to us? I questioned the existential value of art and music and poetry. These had been my tools to understand life. But when Geneviève died, they felt useless to me.”

LL Cool J feature, for The Independent

Phife Dawg came to LL in a dream. “Phife’s like, ‘Yo, that new record with Dre is gonna be dope’,” he remembers. “But he gave me a look – like the Cheshire Cat swallowed a canary – that made me feel like he was bulls***ting me, that what I was working on was s***.” Spooked by the dream, LL called ATCQ’s erstwhile leader, rapper/producer Q-Tip. “I told him, ‘I want us to work together on an album. I want pickle juice, hot sauce, crispy skin on the chicken. I want pimentos in the potato salad – spice flavours.’”

Eminem review, for The Independent

“Much of The Death Of Slim Shady resembles a Telegraph op-ed: the ham-fisted mashing of people’s buttons, the blethering about “the PC police” and “Gen Z” coming to get him. Anything, it seems, to get a reaction. On “Habits”, Mathers spits that his critics are “mad because they can’t tame me” – but there’s nothing edgy about these creaky routines. Like many who harp on about a “woke mind-virus”, Mathers is the one who sounds like he has brainworms, forever bleating about pronouns and, on “Road Rage”, offering the entirely unsolicited information that his “dick just won’t expand” around trans people. OK, mate.”

Chaka Khan feature, for The Independent

“I just liked I Feel For You, and I recorded it, and I went home,” she says. “That night, Arif called in the rapper [Grandmaster Melle Mel]. His move, not mine. I came in the next day and heard the rapper’s introduction and … I was devastated. This guy, saying my name over and over, and what he wants to do to me … I was like, Oh, hell no. ‘Don’t worry my dear, it will be a hit.’ I just shut up then, because as I always told Arif, I can’t tell a hit from a non-hit – I love all my songs – but he was trained to do that. And that track did its thing, it kept me current.”

Yasmin Williams feature, for The Guardian

“My mom said: ‘You’re stuck in the house, so just concentrate on your music’,” Williams remembers. So she poured her anxieties over “the horrible political climate, the George Floyd protests, police violence across the country and the pandemic sending everyone insane” into a batch of new compositions. “I couldn’t put what I felt into words, so I just played. Whatever songs happened, happened.”

Caribou live review, for The Guardian

“Tonight offers glimpses of Snaith’s more wildcard phases: mesmeric, psychedelic krautrock epic Sun; the gamelan-clanging space-funk of Bowls. The lion’s share of the set focuses on new material, however, which takes a more direct route to dancefloor nirvana, one Snaith has been signalling since 2014’s Our Love and his releases as side-project Daphni.”

Minnie Riperton feature, for The Guardian

“This slow-burning funk session turned up the temperature with Riperton’s suggestion: ‘We should be one / Inside each other.’ There’s a powerful spiritual element at play here, but her repeated request of ‘will you come inside me?’ made Donna Summer sound like the Singing Nun.”

Devid Remfry feature, for The Guardian

What was Dee Dee Ramone like to draw? “Terrible, because he’d load himself up with whatever it was he was on and be twitching all the time,” Remfry replies. “I really wanted to capture his tattoos, but his arm was never still long enough for me to draw them properly. One time he took me down to his room, and when he opened the door I was hit by a wave of this substance, whatever it was, like a pot of the most potent glue. It was hanging around the room itself – you got high just breathing in. God knows how he lived as long as he did.”

Limbo District feature, for The Guardian

“Jeremy was a great friend and mentor,” Stipe says. “The person that I became, the public persona of Michael Stipe, I owe to him. He taught me how to dance, how to laugh at myself, how to dress. At the time I thought he was the first love of my life – although it turns out I was just infatuated with him,” Stipe laughs.

X feature, for The Guardian

“Rumours circulated, like, ‘There’s this awesome place with a swimming pool where we can skate and drink beer, and nobody knows it’s there’,” remembers Cervenka.

“I don’t think it really was Flynn’s mansion,” adds Doe, “but we all snuck into the Hollywood Hills. The shit hit the fan pretty quickly: cop cars showed up, and Exene and I slid down the hill and got separated.”

Ghostface Killah feature, for The Guardian

“Everyone’s got fat asses now, too – that’s an invention. I’m not saying that’s one of the greatest, but I’m just saying: damn. Like, I was remembering when I was younger, girls had little butts, no butts – none whatsoever. Now, everybody got a butt. You know what I mean?”

Beastie Boys feature, for The Guardian

“The Beasties weren’t interested in expensive gear – they preferred cheap vintage finds with personality. Such as Yauch’s Univox Super Fuzz distortion pedal, which featured on Sabotage and Pass the Mic, and made his bass sound monumental on this brilliantly Cro-Magnon funk-rap-rock beast. ‘When Mr Super Fuzz showed up,’ wrote Ad-Rock, ‘shit got different.’”

Steve Albini feature, for The Guardian

“Mclusky Do Dallas sounds like we sounded as a band, for better or worse, and what leaps from the record is so much energy that you really feel like you’re there. And that’s because of Steve’s understanding of the scientific principles of where to place a microphone, but also because he had empathy, he knew how to listen to a band.”

Yaya Bey feature, for The Guardian

“My dad taught me how to listen to music. How to relate to it, how to find your humanity in it; the fragility of just being a human and being alive. We don’t talk about how fragile life is, because we’d all be fucking wrecks if we focused on that. But in music, the vulnerability of life exists in a visceral way, in a way we can swallow. My dad taught me how to be present with that.”

The Lemon Twigs feature, for The Guardian

“Our parents would sit us in front of old Ed Sullivan Show appearances by the Dave Clark Five, the Lovin’ Spoonful and the Beatles as kids. The Beatles meant as much to us as superheroes or NFL stars to other kids. We could not relate to anybody at school. [laughs] We were obsessed with understanding chord structures and figuring out the architecture of recording. It was like being part of a secret club.”

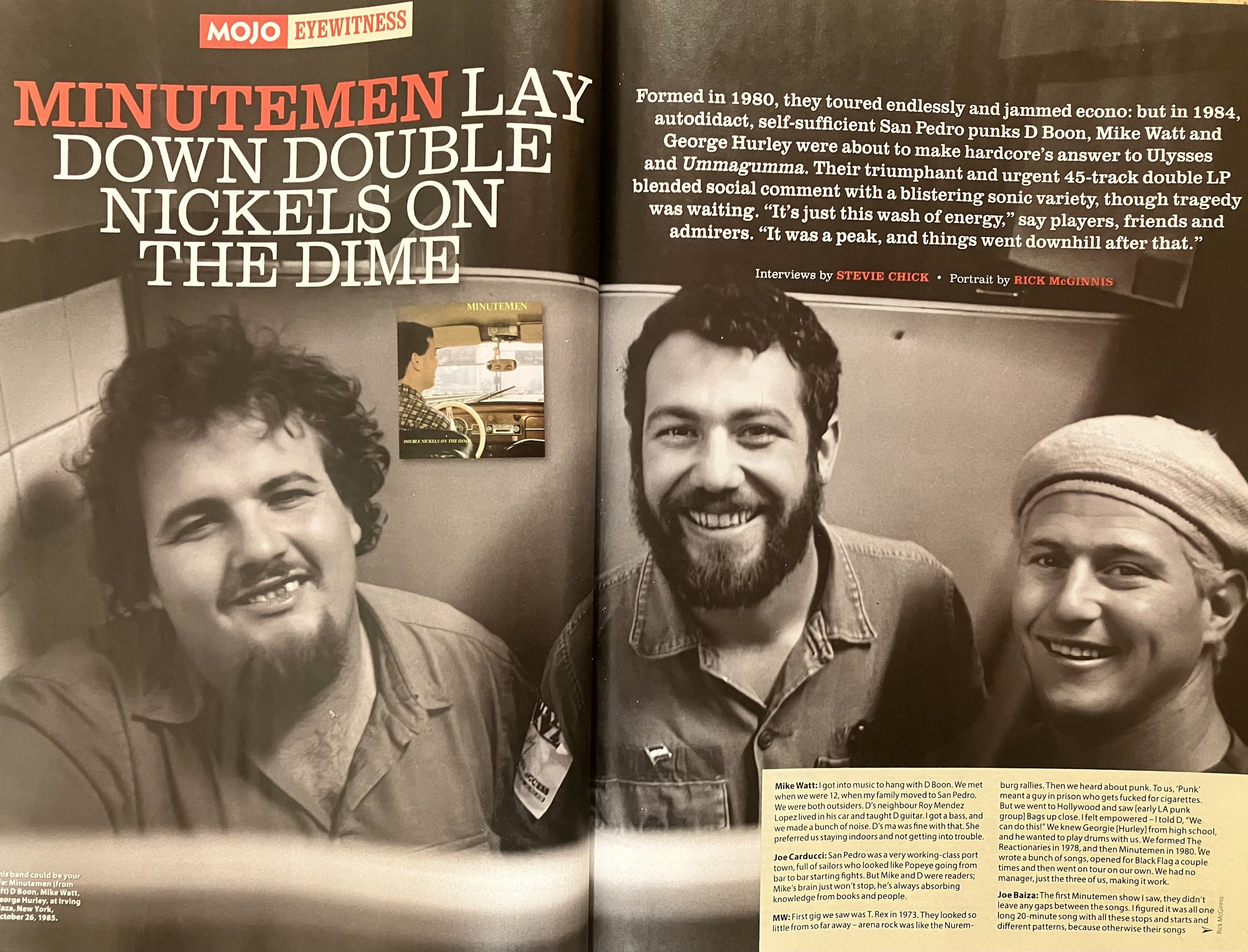

Minutemen feature, for MOJO

“We knew genres were gulags, fuckin’ ‘Berlin Wall’ shit. We’d play what we wanted, we didn’t pay attention to any constraints. Punk taught us music was about expression. D was picking ideas up from R’n’B, making room for the drums and bass by playing this trebly, staccato, clipped guitar, like Curtis Mayfield, like John Fogerty, like Scotty Moore. Our lyrics were us thinking out loud.”

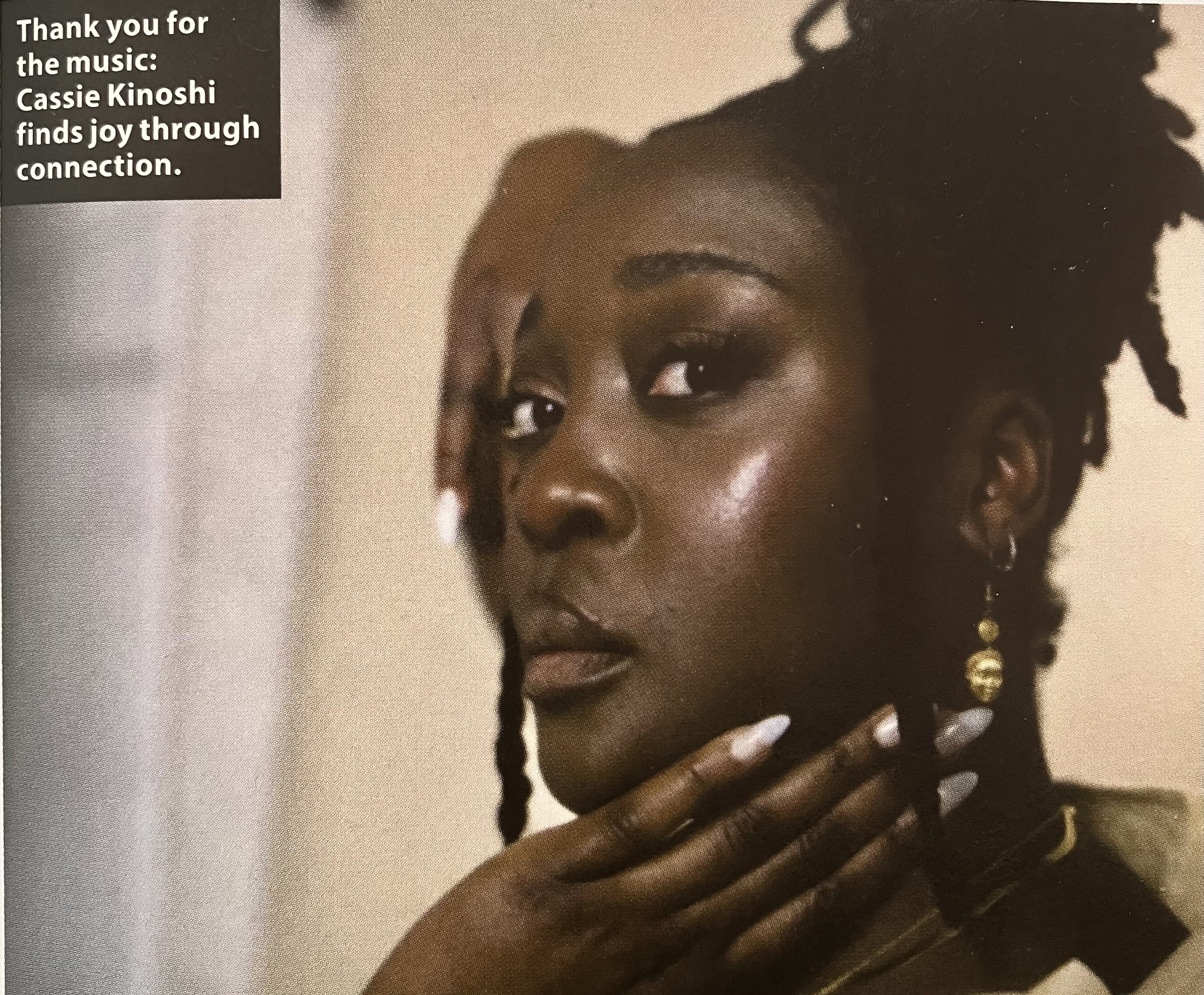

Cassie Kinoshi profile, for MOJO

“Jazz in the UK had become divided by class, it wasn’t very accessible. The music now enjoys a better platform, the space to become a social music again. It’s no longer centred around elitism and passive listening, it’s more about community and dancing and togetherness, about sharing a message.”

Think-piece, for The Independent

Joni Mitchell’s genius was underestimated in her day by a misogynist rock media. But her subsequent critical renaissance has prompted an ongoing series of Archives box-sets, uncovering priceless treasures like her original 1963 audition tape for Saskatchewan radio. Alice Coltrane was disregarded by much of the jazz press when she pursued her own fearless career in the wake of husband John’s 1967 death, but recent years have witnessed a reappraisal of her exhilaratingly challenging output, kickstarted by Luaka Bop’s excavation of her 1980s devotional music.

Sonic Youth feature, for The Independent

“Sonic Youth always had a lot of luck – an ability to be in the right place at the right time. We were pretty skint. But we knew we had something special. We were getting very little traction in the US.” American music magazines like Rolling Stone were mainstream-focused and paid little attention to groups like Sonic Youth. “But the UK had all these weekly music papers looking for stuff to write about. We had to get there. So, we made it happen.”

Brittany Howard profile, for The Independent

“I just came out of the womb different. I was a late bloomer; I was tall; I had kinky, curly hair, and no one else I knew did. It all just made me really resilient. People say I seem really confident, but they don’t understand what I’ve been through. I’m like a piece of hot metal that’s been strengthened by being thrust into cold water. I’ve been tempered by life.”

Sault live review, for The Guardian

All this mystery would be meaningless were the music not so consistently remarkable. Their eclecticism is dazzling but grounded in substance, their anthems aiming at the feet and the heart with equal accuracy: the choir-led symphonics of Time is Precious; Simz’ writhing, irresistible Fear No Man; the fearsomely in-the-pocket Warrior. It’s a lot. Given the buzz that’s built around Sault these last four years – and the £100 ticket price – it had to be. But this immersive, eclectic, astonishing three hours posit Cover and collaborators as time-travellers traversing Afro-legacy and Afro-future, masked visionaries cycling between humility and audacity.

Madness profile, for Record Collector

The sort of golden ticket you’d build a time-machine to experience, the 2 Tone tour was a travelling showcase for the Specials’ label, traversing the UK across 40 dates, beginning at Brighton’s Top Rank on October 19, 1979. “The Specials were the best live band I ever saw,” remembers Suggs. “We’d hang out and watch them every night, dancing about on top of the speakers. It was fucking maniacal – the balconies in those old theatres looked like they were about to collapse with everyone jumping up and down. On the tourbus you had the people who drank up the front, the people who puffed down the back and the people with speed in the middle. And we were running up and down the aisle of that bus, not quite sure what bit we wanted to be in. How young we all were… like kids. A tremendous time.”

The Kills profile, for The Independent

When Covid hit, Hince retreated to his home in LA and lost himself in projects. “I had a manic episode for two years, and I loved it,” he grins. “I lived like a cat – I’d just continue working and making things, fall asleep for a couple of hours and then wake up and start again. Time didn't matter. I'd open a bottle of wine at seven in the morning! I was learning to embroider, I bought an old photo booth, I started making my own trousers...”

Young Fathers live review, for The Guardian

“The group jitter on to the unadorned stage like unstable elements, casting vast shadows of their endlessly dancing bodies on a grimy canvas backdrop. It evokes Talking Heads’ concert movie Stop Making Sense, and Young Fathers are similarly all energy and ecstasy.”

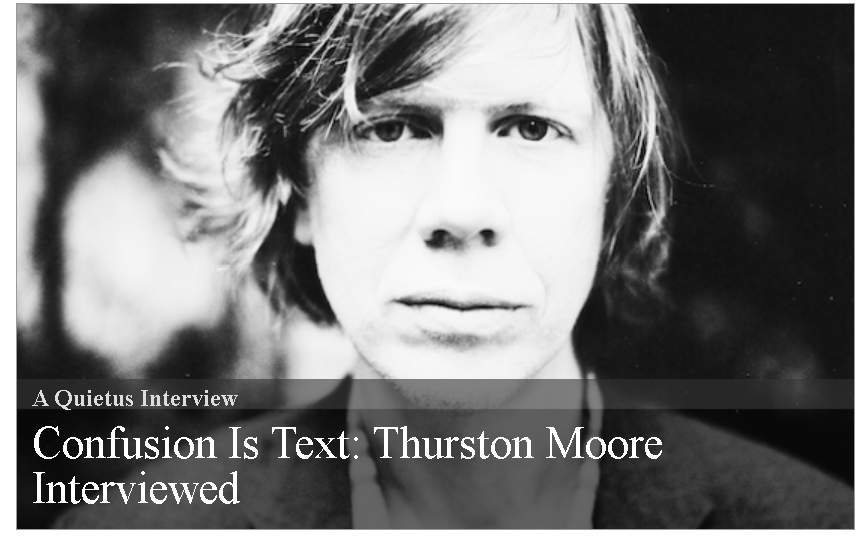

Thurston Moore interview, for The Quietus

“Sonic Youth no longer existing was defined by Kim and I getting divorced – like, 'We broke up, has the band broken up as well?' That became the narrative, though there was never anything official announced. In that sense, it's like we never broke up. And I kind of like that. By calling the final album The Eternal, it allowed for it to be this 'POOF!' into the magic universe of foreverness.”

Elephant 6 interview, for The Guardian

“We were building a universe that was lo-fi, personalised and highly experimental. We worshipped Brian Wilson, Brian Eno and Yoko Ono. We mashed-up psychedelia and pop and punk and experimentalism. And we had each other to buoy us, so we didn’t need the rest of the world’s approval.”

Slowcore feature, for The Guardian

“We started breaking things down, exorcising these nasty qualities coming from grunge. I wanted – needed – to say things one could easily feel embarrassed about, and the countervailing mechanism was restraint. Our songs sounded better slow and stripped down, when we tried to say more with less.”

Ben Howard interview, for The Guardian

“A flood of anxiety came with the first attack – it felt like a falling apart. But the second time, I knew what was happening. For an hour, I just existed in a world of confusion, light, sound and feelings. I was able to sit and wonder about this rogue thing, this brief glimpse into something really strange and surreal.”

billy woods interview, for The Guardian

“The business ground to a halt. An important personal relationship ended. A decade of incremental progress seemed to culminate in crushing defeat. It was like, ‘the plane’s crashed, you’re either gonna drown or you’re gonna swim. It’s on you’. To rescue myself, I was forced to swim.”

Billy Valentine interview, for The Guardian

“The Reagan years saw poorer communities suffer. Taxes were rising on us, and the rich were getting richer, and Black people were being oppressed by law enforcement … Something needed to be said, and I tapped into the social commentary of the 60s, of the Last Poets, of Donny Hathaway.”

Roy Montgomery interview, for The Guardian

Scenes from the South Island was “about being away from your home country. I’ve never tired of the imagery that generated the album, and those landscapes are still places I go to, physically or in my mind. Those visions of space and atmosphere – the absence of busy, human life – populate a lot of what I do. It’s regenerative, an existential thing.”

Lora Logic interview, for The Guardian

Logic relocated to a squat in Stoke Newington. “There was no kitchen, no bathroom,” she says, laughing. “We’d bathe at the Victorian bathhouse in Ladbroke Grove. There wasn’t much electricity. We’d build fires to keep warm, live off bread and cheese. And there was a DJ on the floor below who played loud funk and reggae all hours. I loved it.”

Mimi Parker obituary, for The Guardian

On ‘In Metal’, she used the practice of bronzing a baby’s booties as a metaphor for the intense vulnerability that follows having a child – the fear they may come to harm, the sensation that parenthood itself is a fleeting experience, quickly ebbing away – singing ‘Partly hate to see you grow / And just like your baby shoes / Wish I could keep your little body / In metal’. The song was a study in Low’s ability to create music that is both beautiful and unsettling at the same time.

Big Joanie interview, for The Guardian

“People call us a lot of things, but we’re still punk. Because, for me, ‘punk’ means freedom. It’s open, and constantly growing. When I was a teenager, I wanted to sing along with music but I was very shy. But now I sing all the time. To be able to put that noise and anxiety and energy out into the world – that’s the release I always needed.”

Gilla Band interview, for The Guardian

Duggan says they wanted to channel the elastic surreality of the dreamspace. “Reality gets distorted in a dream. An elephant might walk past you and say: ‘How are you?’ and you just accept it.” That surrealism is most present in Kiely’s lyrics. His characteristic unsettling absurdist imagery and dark wordplay abound, with recurring motifs of decaying teeth, sea creatures and balding barbers.

Feature on the influence of Star Wars’ Cantina Band, for The Guardian

“Our conversation with Björk was really inspirational, imagining music in another world. Like, what would music sound like without any contact with jazz? It’s been a reference point for our work ever since – writing music for some other place, imagining a world where music would sound like the music we make.”

Arab Strap interview, for The Guardian

“Every single song in Arab Strap’s first 10 years, except one, was autobiographical. I had rules that everything had to be true and honest, and I stuck to them pretty rigidly until we reformed. The truth is, life gets less interesting as you get older. I don’t want to write songs about the school run or having a nap.”

Herbie Hancock interview, for The Guardian

“ I’m working a lot with younger people. They are the future, and I’m always looking forward. Musicians from the generations before me helped and encouraged me, and showed me mistakes in my thinking about the structure of a song. I’m at that point in my life where it’s time for me to pass the baton on to younger musicians. But I’m not ready to leave just yet.”

They Hate Change interview, for The Quietus

“At a certain point I felt like I didn’t want to write sad songs about my gender fluidity, because I don’t want to be sad about it – it is not a thing that is sad. And I shouldn't be sad about it, you know? I’m going to talk about it in a very real way, and that doesn’t just mean being sad about it. Some days I’m really charged-up, some days I’m really feeling myself, just like everybody else. And some days I might feel a little bit lower, just because, but some days I got a ‘S’ up on my chest, like I say on ‘Some Days I Hate My Voice’. It’s like, Yo, let me talk my shit right.”

Mahalia Jackson profile, for The Guardian

At Jackson’s urging, King delivered the greatest speech of his career. “Listen back to it,” urges Fana Hues. “His intonation was like he was singing.” Jackson had once patterned her singing on “the way the preacher would preach in a cry, in a moan”; now the nation’s most famous preacher was following her lead.

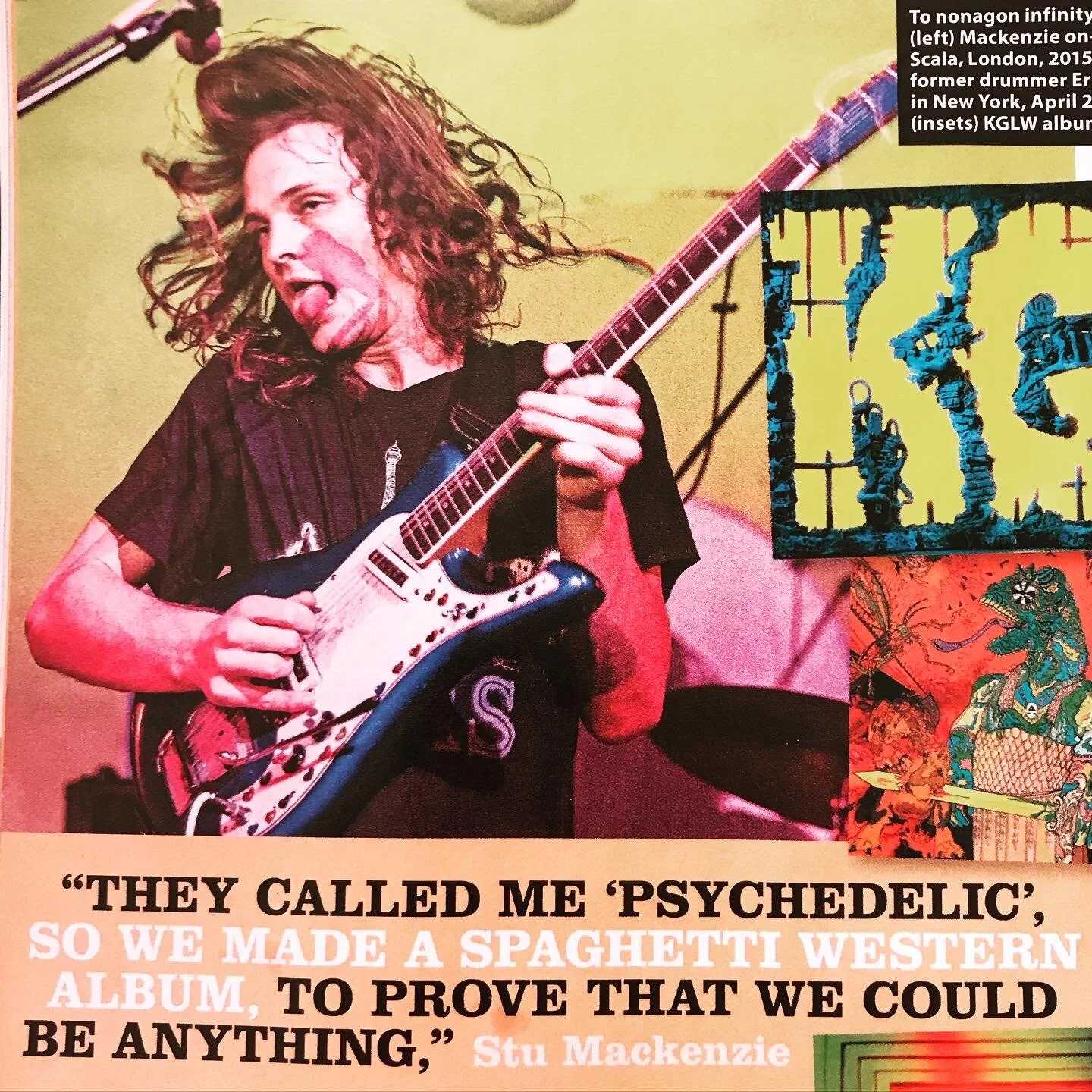

King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard interview, for The Guardian

The 18-minute krautrock rollercoaster The Dripping Tap had existed as a soundcheck jam before the pandemic, but had been sidelined by lockdown. “I knew, as soon as we could get together and jam again, that was the first thing we’d record,” says Mackenzie. When that blessed day finally arrived, in June 2021, he remembers feeling “weirdly nervous” as the group gathered at their new HQ in the Melbourne suburbs. “We had to hug and just shoot the shit for a bit, cos we hadn’t interacted much with the outside world. But what we really wanted to do was just make loud music together. It was so pure, like a Jackson Pollock painting. It was everything we’d missed so much for all those months: the interplay, our synapses connecting, that ephemeral aspect of improvisation.”

Sault album review, for The Guardian

Dean Josiah Cover’s considerable ambitions peak on the epic Solar. Across 13 riveting minutes, it draws into its orbit repetitive synth arpeggios and inventive choral work suggesting Terry Riley’s A Rainbow in Curved Air and North Star-era Philip Glass; soprano voices singing melodies that evoke John Coltrane’s Naima; and passages of star-gazing orchestral music that recall the sublime, soulful gospel of Donny Hathaway’s I Love the Lord, He Heard My Cry. This fusion of unlikely elements creates an earthy pocket-concerto that’s cerebral and creatively adventurous while harbouring potent emotional power. It’s a trick Air pulls off again and again.

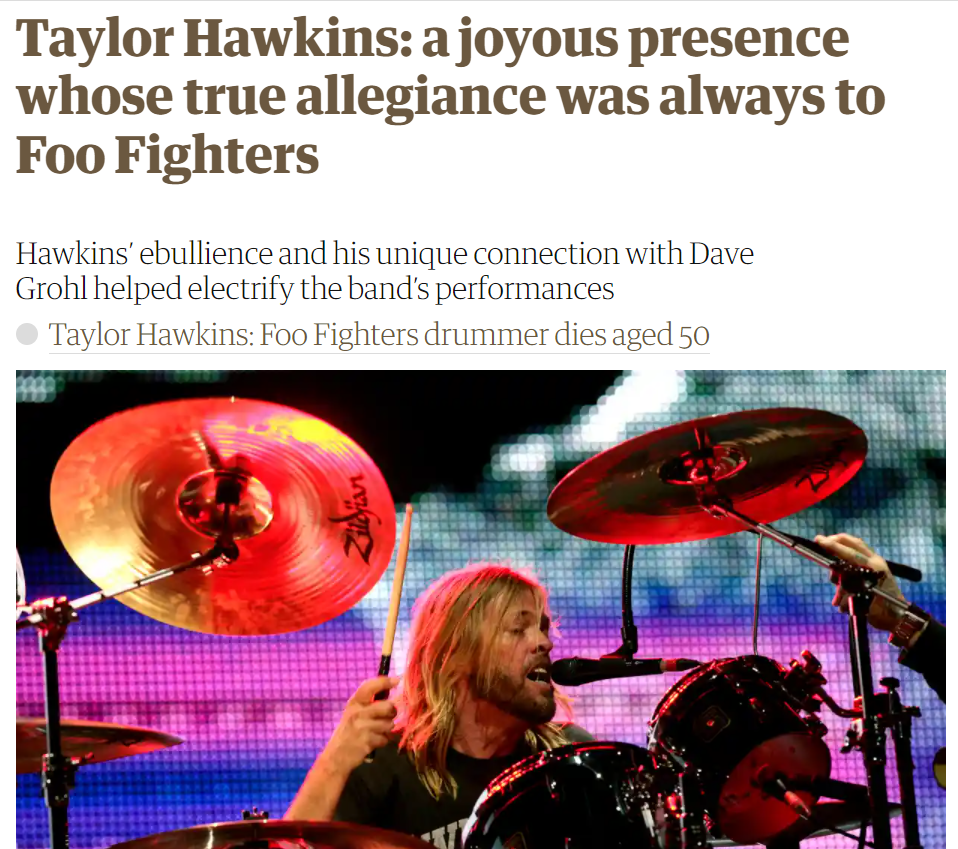

Taylor Hawkins obituary, for The Guardian

Grohl himself had always seemed the goofy, sunshine element amid the darkness of his previous group, Nirvana. Now, in Hawkins, he’d located his own Dave Grohl figure for Foo Fighters. “Taylor and I are like brothers,” he said, years later. “The two of us are best friends. You only find so many best friends in a lifetime. Taylor and I wound up being separated at birth.”

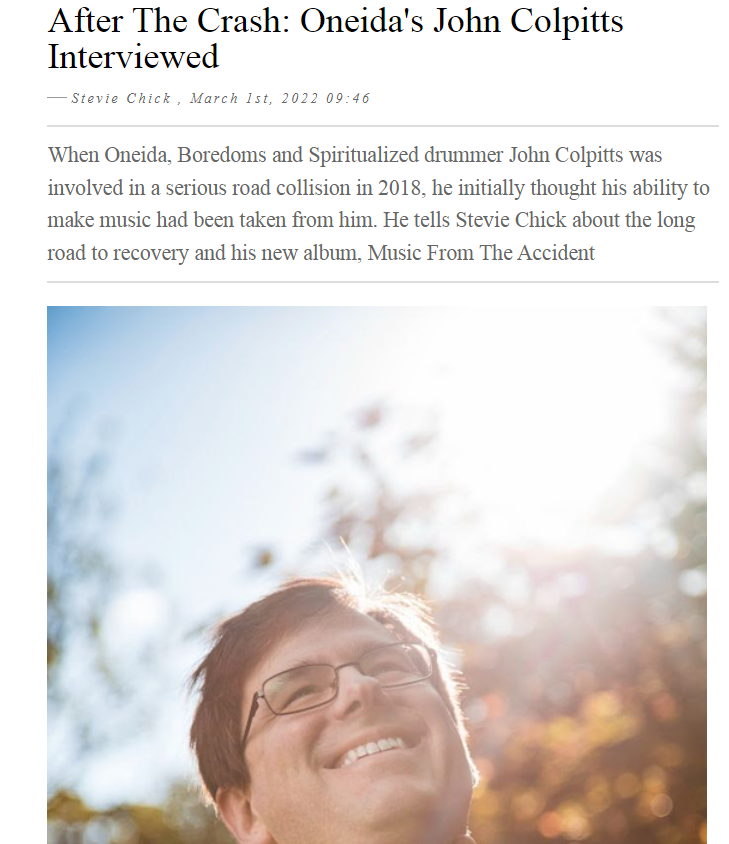

John Colpitts, profiled for The Quietus

“We became our own inspiration. Oneida can't really copy anything, we just don't have the ability. We're not skilled, we're not chameleons. So we would have an idea, an aspiration, and just attempt it, and it would become something else, something that was just ours. Nobody is psychedelic like Oneida. Some of the records sound more classically psychedelic, but we don't sit there and jam with a wah-wah and echo. Our sound just became more ‘us’. And that just came from playing together a lot, and being open and recording a lot. Can and Sonic Youth had their own studios, they would go there regularly and record everything they did, and we had that too. That's how that voice came out.”

Mark Lanegan obituary, for The Guardian

“It was the end of a nightmare that had lasted for years and years. Nobody likes to believe they need anybody’s help in anything, and the smarter you are – and I’m not smart – or the tougher you are – and I thought I was pretty tough – the more trouble you have. The smartest guys I ever met are not around any more because they thought they could think their way out of an unthinkable situation, and the tough guys have to just be beaten up repeatedly. And some guys just never do make it out.”

James Smith of Yard Act, profiled for The Guardian Saturday magazine

“The state of this country, and the world,

can quickly get you into a spiral of Everything Is Bad. But it’s not. The good moments don’t exist without the bleak shit. We can’t eradicate misery and depression, we’ve got to coexist with it.”

Ethan Miller of Howlin’ Rain, interviewed for The Quietus

“There’s a whole other album’s worth of Field Recordings From The Sun-style music out there somewhere. But when we listened back to the full thing, we chopped it down to barely an album’s length. We were like, ‘Dude, that’s enough’. It’s a complete nuclear meltdown. Like, there’s nothing left but scorched earth after those 36 minutes. That’s the statement.”

Summer Of Soul feature for The Guardian

“Joy is an element that gets lost too often in the narrative of Black America,” ?uestlove says. “You see the bloodshed, the pain, the tears and the struggle – you learn that we got tased, we got bit by dogs, we got shot. But Black joy is a legit entry in our story. It’s where our creativity comes from, our Afros, our fashion and our music. It’s important to show Black joy as well.”

Low, interviewed for Loose Lips Sink Ships

“It seems like it’s just normal now, with Twitter, to tell someone ‘You suck!’ or ‘Fuck you!’, to send that energy out there. I could definitely tell, when we got done, that there were people who were really… not into it. I was picking up my gear and could hear people yelling at me. Something’s creeping into American culture… I guess it’s afterbirth from the last several elections just being so hateful…”

Part Chimp, reviewed for the Guardian

Purveyors of bone-simple dirges and fearless explorers of the higher reaches of volume, they provoked as much grinning as helpless headbanging at the All Tomorrow’s Parties festivals where they found a natural home, and revelled in conceptual gestures such as delivering terrace chants over a noise like Black Sabbath wading though creosote.

The Offspring, interviewed for the Guardian

Noodles’ faith in the Offspring’s newfound success was shaky enough that he was reluctant to quit his day-job as custodian at an elementary school in Anaheim. “We had a video on heavy rotation on MTV, and I’d be sweeping up trash out back of the school, and kids would walk past and be like, ‘Man, what are you doing here? I saw you on MTV this morning!’ I ended up asking for a three-year leave of absence – I was worried that if the band flopped I’d have to start my career at the bottom rung of the ladder again.”

Adam Sherburne of Consolidated, interviewed for the Quietus

“Every night I was surrounded by often-drunk and possibly armed skinheads who wanted to take me to task, or recruit me, or ask me if I was gay or whatever. I had to deal with all these bizarre cavemen behind the bus after the show, to de-escalate and find a human agreement point, to break off from motherfuckers who were very aggro.”

Dinosaur Jr remember their turbulent early years, for MOJO

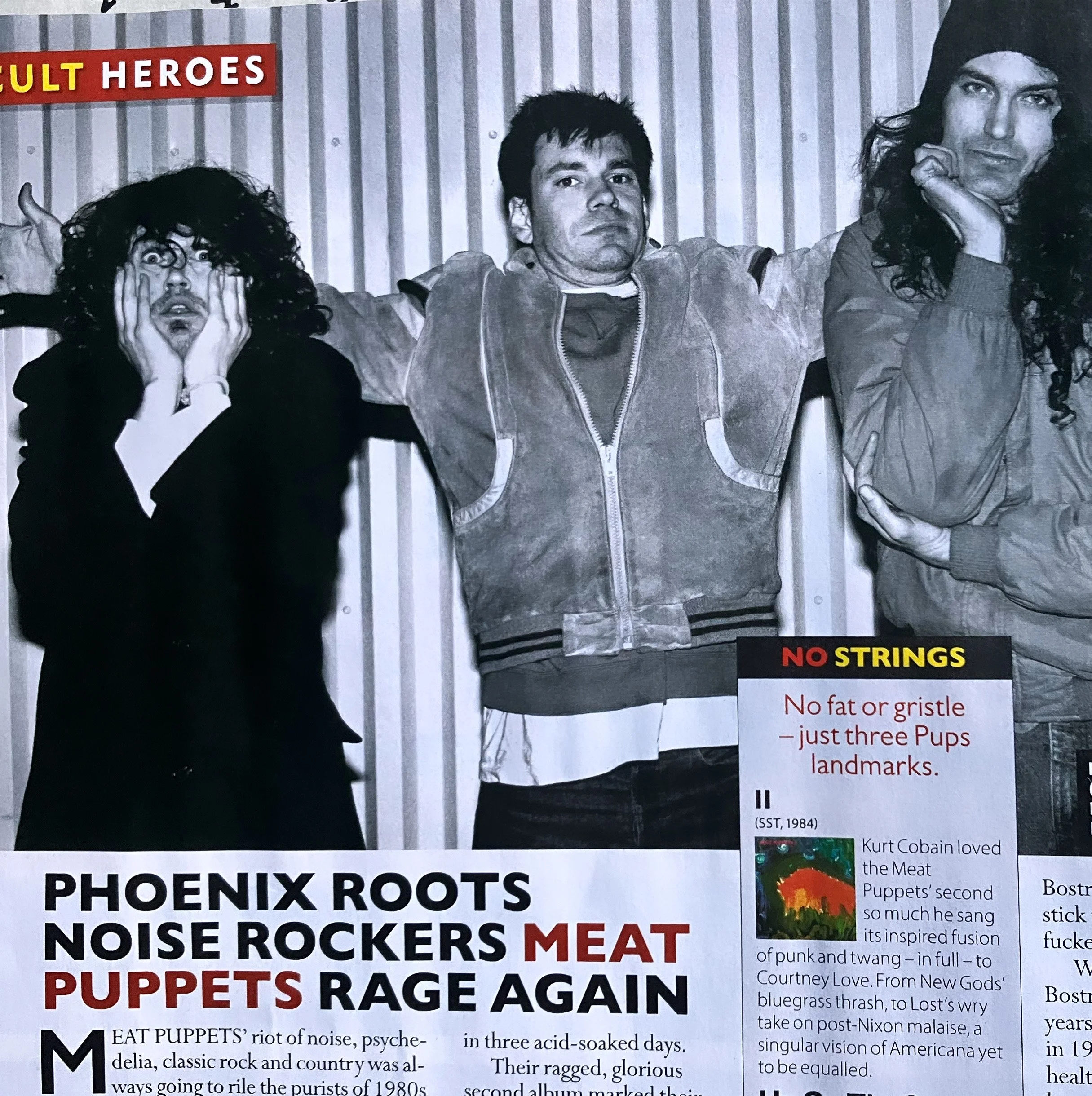

“We were obsessed. We wanted to make good music, and that was all that mattered. We weren’t some buddy movie, drinking beers and rocking out. We weren’t friends. We loved the Minutemen, Husker Du and the Meat Puppets, and our ambition was to tour like they did and sign to SST Records, the label they were on. That was our goal. ”

MF Doom obituary, for the Guardian

“In a genre where ego was all, Dumile remained laid back but still dominated as he broke tempos and rules. His lines dripped black humour and stoner-friendly cultural references, but the mind assembling them was wicked sharp, stacking up multiple rhymes like Super Mario power-ups, and fond of meta-textual intrigue.”

Lee Thompson discusses Madness’s Absolutely, for GQ

“Embarrassment was about my sister having a mixed-race baby and how various members of my family reacted to it. I wanted it to be right. I didn’t want to upset her or my relatives, because most of them were positive about her baby. But some of them were like, ‘Woah! This is taboo. What have you gone and done?’”

The RZA and Sharleen Spiteri on their friendship, for the Guardian

“We had to find a different studio to finish the track the next day, as this wee engineer banned us from Quad Studios. Our management called and were like, ‘What the fuck went on last night? Apparently there were people all over the studio and youse were all high.’ And I was like, ‘We were making a record!’”

King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard, profiled for MOJO

“I’m a sci-fi dork at heart. Nowadays, I can sit through a movie about relationships or whatever, but years ago I connected better to fantasy. I find sci-fi a useful writing tool – it’s fun to world-build. Like, I can’t write another love song – they’ve all been written. But creating my own interconnected world… That’s just so much fun.”

Omar Rodriguez-Lopez on the music that made him, for the Quietus

“‘Los Ejes De Mi Carreta’ is a classic, and it's played all around the world, and my dad played this on guitar all the time, at parties, on birthdays, just sitting around drinking. According to him, when my mother was pregnant with me, he would hug her like Patrick Swayze hugging Demi Moore in Ghost, from behind, putting the guitar on her belly and playing it. I literally heard the reverberations of this song while I was in her belly.”

Bob Mould, profiled for the Guardian

“The words on this album are blunt. This is no time to be oblique or allegorical. This evil resonated so clearly through my body, I had to write to cancel that resonance out. It’s like when my tinnitus is really bad, I have to go the beach, because the only thing louder than my tinnitus is the ocean.”

Looking back on the Fania Allstars’ breakthrough, for the Guardian

“Gast communicated that salsa was the music of the people via Ismael Miranda singing with Orquesta Harlow at a bustling impromptu block-party, Ray Barretto serving cones of freshly shaved ice to kids, and a bloody, stomach-turning cockfight down a back alley.”

Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever, interviewed for the Guardian

“People think of our songs as really sunny, driving-to-the-coast-with-your-elbows-in-the-breeze music. But Hope Downs is all about claustrophobia and bewilderment. The album’s named after this huge mine in Western Australia, this massive hole in the ground. And 2016 was this year where you felt like you were standing on the edge of this great abyss wondering, ‘What next? Where are we going?’”

On whether or not Wind Of Change was a CIA plot, for the Guide

“The CIA saw rock music as a cultural weapon in the cold war. Wind Of Change was released a year after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and became this anthem for the end of communism and reunification of Germany. It had this soft-power message that the intelligence service wanted to promote.’”

On the new wave of TV cookery stars on YouTube, for the Guardian