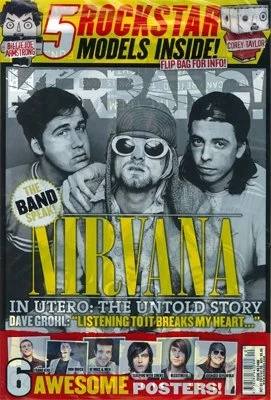

Nirvana: In Utero

Dave Grohl and Krist Novoselic on the making of Nirvana’s final album

In Utero: In Their Own Words

“The space of time between the release of Nevermind and the end of the band was really just a few years,” says Dave Grohl, of Nirvana’s rocketing hurtle from obscurity to superstardom. Their debut album, 1989’s Bleach, famously cost just over $600 to produce. Their second album, 1991’s Nevermind, topped the Billboard charts three months after its release and went on to sell 30 million copies.

That kind of upheaval would be a headfuck for any artist, let alone Kurt Cobain, the sensitive, mixed-up little guy fronting what was, by 1993, the biggest, most important rock band in the world. Already suffering from depression and a debilitating drug-addiction, and possessing a most ambivalent attitude towards his newfound fame, Cobain would respond to this rollercoaster ride through Nirvana’s third full-length, which remains, two decades on, one of rock’s darkest, most uncompromising, most powerful albums of all time.

Here, in the words of the surviving members of Nirvana, is the story of In Utero.

Dave Grohl: When Nevermind came out, we were in the van on tour, playing tiny places that held anything from a hundred to four hundred people. By the end of that tour, everything had been upgraded, and we were playing venues with capacities of several thousands. It happened so quickly that, by the beginning of 1992, we decided to stop. Nevermind was selling millions and millions of copies, and we were basically hiding from everyone, because we didn’t know how to deal with that success.

Krist Novoselic: Nirvana had been this obscure little band, living out in Tacoma and Olympia, doing our thing. After Nevermind, we were ‘famous’, we were ‘successful’, we could buy houses. There were a lot of changes going on. We were in the middle of a whirlwind.

Dave: We were used to living together in confined spaces before the band got big, and then, once Nevermind blew up, we all spread out. I went back to Virginia, Krist was up in Seattle, Kurt moved to Los Angeles. Things just changed. We weren’t as close.

It’s no secret that Kurt was battling drug addiction. And there was tension within the band over some business matters. It all seems a little clichéd now – you’ve probably read a fuckin’ million rock’n’roll biographies that are all the same – but it actually happened to us. We didn’t know what to do next.

Krist: We had one refuge from it all, which was getting together and just playing. We’d leave all that other stuff outside the rehearsal room door, and just do what we did, playing music together.

Dave: The only logical progression was to make the next album.

From a series of rehearsal sessions late in 1992 – some tracks from which appear on 2004 box-set With The Lights Out, and on the 2013 In Utero deluxe reissue – sprang the songs that would form Nevermind’s follow-up. But it soon became clear that this new album wasn’t going to sound anything like Nevermind. Indeed, Kurt had already begun telling interviewers that Nevermind sounded “too slick”.

Still smarting from the punishing sessions with producer Butch Vig to perfect Nevermind’s polished sound, reeling from accusations of “selling out” from po-faced punk zines like Maximum Rock’n’Roll, and not exactly enjoying the fallout that came with becoming a radio-friendly unit-shifter, Kurt Cobain would ensure that Nirvana’s third album could never be mistaken for “Nevermind Part II”.

Dave: Each of us processed the experience of Nevermind’s success in different ways. My take was, ‘Wow, you mean I don’t have to go back to work at the furniture warehouse again?’ I was fucking relieved that I had finally made some sort of mark with my music.

But I was the drummer, the one whose face was covered in long black hair and hidden behind a rack of toms. I could walk in the front door of a Nirvana concert and never be recognised. It was kind of ideal for me. On the other hand, it was much more intense, much harder for Kurt. I think some people are built for that – to sustain or survive that – and some people just aren’t.

We had worked really hard, every fucking day of the sessions, to make Nevermind what it was, recording and rerecording songs. That album’s crafted, honed. And the new album would be much more visceral, more emotional, more immediate. It was our backlash to everything that had happened, to the experience of Nevermind.

Krist: We had some unused songs from the Nevermind era, Kurt had written some new songs, and we jammed out some new songs. It didn’t sound like Nevermind. Listen to the stuff on With The Lights Out: we loved playing weird, twisted, heavy rock, because we grew up on mid-80s punk-rock, bands like Flipper and Butthole Surfers. Kurt was a great songwriter, he loved melody and had a knack for catching a hook. It all came together with this weird, edgy, melodic heavy-rock music. That’s Nirvana’s sound, right there.

In a move which signalled Nirvana’s intentions for the new album from the off, the group rejected all of the ‘big name’ producers suggested by their label, Geffen, and sought instead the services of Steve Albini. Independent-as-fuck, former Big Black frontman Albini was famed equally for his ability to make underground rock groups sound amazing on a tiny budget and his vocal disdain for the music industry. Grohl later admitted that the choice of Albini as “engineer” of the new album (Albini habitually refused the title of “producer”, along with any royalties on the albums he recorded, on moral grounds) made their A&R man Gary Gersh “freak out”.

Krist: Steve Albini was Kurt’s idea, he was a big Albini fan. He was enchanted with the Pixies’ debut album Surfer Rosa when that came out in 1988; he was in love with the snare sound on that record.

Dave: Steve was a hero of ours, it was always a dream of ours to work with him, ever since hearing Surfer Rosa’s drum sound, or the guitar on Two Nuns And A Pack Mule [by Albini’s controversial group Rapeman], or the industrial fucking noise of Big Black. We loved that guy. And there was something about his ultra wicked, cynical humour that we connected with.

But for a band like Nirvana, it was kind of a stretch for us, to go to the most opinionated underground punk-rock producer and say, ‘Hi, we just sold fuckin’ three million records, will you make our next one?’ We basically wanted his approval. Not only did I want his drum sound, I wanted him to look at me and say, ‘Okay, that guy is a good drummer, and this band is real.’

Steve Albini: [letter to Nirvana, November 1992] “The best thing you could do at this point is exactly what you are talking about doing: bang a record out in a couple of days, with… no interference from the front office bulletheads. I would love to be involved.”

With Albini onboard, in February 1993 Nirvana relocated to Pachyderm Studios in remote Cannon Falls, Minnesota, to record the new album. They’d booked two weeks’ worth of sessions, during which they would work hard, work fast – and, perhaps surprisingly, have a lot of fun.

Krist: Cannon Falls was really isolated, geographically. Nobody recognised us there. There was nobody around to recognise us. Just some cows, and maybe a deer walked by every now and again. It was like being in Siberia. And it was crazy cold, bitterly cold.

Dave: It was the middle of winter, and it was thirty degrees below… It was the coldest I’ve ever been in my life, like, so fuckin’ cold that it hurts to be outside. Your skin just stings.

But it was good. There’s some bands who only speak to each other with their instruments. We weren’t at that point yet, but being apart for much of 1992 had fractured the world that we lived in before Nevermind broke big. Coming together again, in that log cabin in the woods… it was fun. We were friends, you know? We were close. There may have been some awkward moments, but for the most part it felt good to get back to it.

Krist: It was a good vibe in the studio, lots of fun, lots of practical jokes. Steve bought this microphone that fit on a phone receiver and could record phone-calls, which is illegal. [laughs] Steve and Dave were always making prank phone calls [alleged recipients of such prank-calls included fellow rock-stars Eddie Vedder, Gene Simmons and Evan Dando of Lemonheads]. And they’d be playing with fire, Dave dousing his baseball cap in rubbing alcohol and setting it on fire to freak us all out. Everything was completely irresponsible. It was just blowing off steam, it was crazy.

Dave: I’m a fuckin’ goof, I’m a jackass. I take my music really seriously, but everything else, I just kind of giggle at.

It was our third album. It was time to get daring. We had no fear of failure – the idea was to go in and get ‘real’. And Steve was the perfect producer for that, his method was to capture ‘real’ moments.

Krist: It seemed like Steve was thinking, ‘Here are these guys in this big rock band – what are they all about?’ But we were well-prepared, we were ready to go into the studio. We nailed those songs. Serve The Servants, the first song on the album, was the first song we recorded with album, and we got it in pretty much one take, too. Steve was standing by the tape machine, arms folded, and we started playing the song. It fell apart at the end, like all the songs do [laughs], and Steve said, ‘That sounds good to me. Let’s do another song.’ And that was it! At the most, it’d be three takes before we nailed a song.

Dave: We were booked in the studio for twelve days or something. I’d already recorded all my drums in three days. So I just sat around and watched TV the rest of the time.

Krist: Steve’s girlfriend Kera Schaley came down to the studio to say hi, and she had a cello, so we had her play on Dumb and All Apologies. There was an ‘off the cuff’ vibe to the sessions. We came up with that big riff in the middle of Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge On Seattle, the bridge, in the studio while recording it. It’s like a classic, formula ‘Nirvana’ thing. We looked at Steve and said, ‘Shall we do it?’ And he said, ‘Yeah! Absolutely! Do it!’ So we busted into it.

We won him over. We played well together. We always played well together.

12 days after they’d begun, the recording sessions for In Utero were complete, and the members of Nirvana once again scattered in their separate directions. In the aftermath, Dave and Krist would have a chance to reflect upon the album they’d just recorded. Listening to Kurt’s vocals, they’d begin to understand the true nature of the songs, and gain a further insight into their troubled friend and frontman via the lyrics to songs like Rape Me, Frances Farmer Will Get Her Revenge On Seattle and Scentless Apprentice, which dealt obliquely with fame, and Cobain’s struggle to make peace with stardom and media intrusion.

Their record label’s response to the Albini tracks, meanwhile (“The grown-ups don’t like it,” Kurt later told biographer Michael Azzerad) would lead to a still-controversial sequence of events that saw Heart-Shaped Box and All Apologies remixed and “sweetened” by REM producer Scott Litt, who also remixed Pennyroyal Tea for a project single release (later aborted upon Cobain’s suicide). Albini’s original mixes can finally be heard on the 2013 In Utero Deluxe Edition.

Dave: Once the drums were finished, we recorded a few overdubs, and then it was just down to Kurt singing. The songs took on a whole new life and aesthetic once the vocals appeared. I had become familiar with the instrumentals, I knew the riffs and I knew the arrangements.

But it wasn’t until I heard the lyrics and the vocals that I realised the overall tone of the album, which was really dark. When you get to know a song before you hear the words, and then you hear what’s being sung, and just shudder… It was strange. I didn’t know what to make of it.

Krist: Kurt was also a painter and a sculptor, he drew cartoons and made collages and strange films… They were always strange. That was his aesthetic. I have this sculpture he did of this weird spirit being [laughs], some tortured soul. That was his aesthetic. If you look at his paintings, his drawings, the cover to Incesticide – he painted that. He was a talented painter. Skilled. It wasn’t a pretty picture, but it had plenty of beauty in it, still. The songs, they always had a darkness, a weirdness.

Dave: Shortly after the sessions, I was back home, and Fugazi were coming through Seattle. I grew up in Washington DC, and I’d known the guys from Fugazi since I was a kid. They came and stayed over at my house, and I played Scentless Apprentice to Ian MacKaye. And Ian heard the lyric, ‘You can’t fire me / Cause I quit’, and he looked up at me and said, in all seriousness, ‘That’s fucked up’. That’s when I really started to realise, like, ‘Oh wow, this is weird…’ Like, the songs were really, really dark.

Krist: Kurt had his ways, he had his aesthetic, and it was always weird, kinda creepy. You can hear that on In Utero, on songs like Milk It. That’s kind of a creepy song, but it’s intense. And it kicks ass. Put that up against any death metal band, that song will kick their fuckin’ ass.

Steve Albini: [letter to Nirvana, November 1992] If you might find yourself in the position of being temporarily indulged by the record company, only to have them yank the chain at some point [hassling you to rework songs/sequences/production, calling in hired guns to “sweeten” your record, turning the whole thing over to some remix jockey], then you’re in for a bummer and I want no part of it.

Krist: I liked the album, I liked Steve’s mix. There was some controversy over the mix, it wasn’t, uh, ‘palatable’. It wasn’t ‘commercial’. I went back and forth on how I felt about it. It was just edgy, an edgy mix. The label wasn’t really happy with it. So we thought, maybe we could, in the mastering, solve the issues with it. In the end, all three of us went to Portland, Maine, and we mastered it with [legendary industry mastering engineer] Bob Ludwig, and he brightened it up.

Could the label have just rejected the album if they didn’t like it? It’s hard to speculate. I really don’t think so. When you’re a big band, you have a lot of leverage. And it was a good record, it had strong songs on it. You still hear songs off that record on the radio today.

In Utero hit record shelves in the UK and Europe on September 13, 1993; a day later, it was released in America, where it sold 180,000 copies in the first week. The album topped both the US and UK albums charts, and would go on to sell over three and a half million copies.

That Autumn, the group added Pat Smear, former member of LA punk pioneers the Germs, as their second guitarist and undertook their first American tour in two years. February 1994, a year after recording In Utero, the group began a six-week tour of Europe, which was cut short by Kurt’s Rohypnol overdose in Rome on March 4. Within a month, Cobain would be dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Krist: Pat made the band sound bigger onstage. And if there were any tensions at any time backstage, there was this new guy there, and he defused things. Pat was so easy-going, he helped keep things easy-going.

Dave: You can imagine, playing those songs every night… It can get to you. That might be one of the reasons the shows on that tour had a little darker a tone than… Well, I can’t say that, because Nirvana shows were always total fuckin’ chaos anyway. But, yeah…

Krist: We really put on a show, on the In Utero tour. We had props from the Heart Shaped Box video onstage, I played accordion, there was a little unplugged section. We’d play songs off Bleach, off In Utero, weird stuff, and people ate it up. Kurt was up there, busting his ass every night. That had to be intense. We were playing hockey rinks, stadiums. It was fun, but it was hard work. I haven’t toured like that since Nirvana ended. I don’t really like it.

Dave: Of all of the Nirvana recordings, In Utero is the most difficult for me to listen to, not only because it was our last album before everything ended, but because just the sound of it reminds me of that difficult time. Because it was a difficult time. Anyone who listens to that record can tell… It’s not a Christmas album.

Krist: I think In Utero might be my favourite Nirvana album. It’s the most honest. It proved we weren’t just a one-hit wonder. Through everything, it came together, and you can hear it on the album: we knew what to do.

Dave: The legacy of In Utero is of a band being true to themselves. Had we gone out and made an overproduced pop album to try and sell another 30 million records, it would have been a lie. And so, In Utero is entirely real.

Every once in a while I’ll hear one of those songs come on the radio, and I’m really proud that when Heart Shaped Box or Penny Royal Tea or Rape Me comes on the radio, it sounds like a fucked up fuckin’ sonic boom. It stands apart from the other stuff on the radio, you can just hear it, and that’s surreal.

But would I sit down with a glass of wine and listen to that album at home? No I would not. It would fuckin’ break my heart.

Robert Fisher on designing the sleeve artwork for In Utero

“I first worked with Kurt on the cover to Nevermind. He wanted a photo of someone giving birth underwater. I showed him some really graphic images of home-births in hot-tubs, but I also showed him the picture of a baby swimming underwater, and he loved that.

“For In Utero, he gave me a postcard he’d picked up on the road. It depicted the ‘TAM’, which stood for Transparent Anatomical Model. We started negotiating to license the image the museum that produced the postcard, but the minute they learned it was for Nirvana, the price sky-rocketed. In the end the label’s lawyers made a deal, for $80,000. As for the concept, Kurt explained that he was really into the concept of childbirth. I’m not sure if you’d say he was envious of women, that they get to bear children, but he did tell me he was really into seahorses, because the male seahorse gets to carry the babies. He was infatuated with the idea.

“As for the rest of the package, the image on the back, with all the dolls and flowers, was something Kurt made. There are photos on the inner sleeve of the Republican Party’s Los Angeles HQ burning down, and Kurt called me as soon he heard that was happening, and told me to take photos of it and put it on the sleeve. And the symbols that run around the outside of the back-sleeve came from a book on symbols and iconography that Kurt owned, symbols that meant something and he wanted on the package. I’m surprised more people haven’t tried to decipher what they mean!

“I’ve been lucky enough, over the years, to work with artists like Beck, No Doubt, Helmet and Weezer. Kurt was really sweet – a little shy, but great to work with.”

(c) Stevie Chick. Originally published in Kerrang!, 2013.